Wednesday, November 23, 2005

Home Again!

A four-hour layover in New York turned into a nine-hour marathon, extending an already long day. I will definitely need time to digest these past few weeks. It was a good trip, a great trip, and intense trip. But it's always good to be home again.

A four-hour layover in New York turned into a nine-hour marathon, extending an already long day. I will definitely need time to digest these past few weeks. It was a good trip, a great trip, and intense trip. But it's always good to be home again.Monday, November 21, 2005

Border Bothers

The problems began when I boarded the Palestinian bus in Jericho. There, Palestinians are separated from their luggage. After a document check by the Palestinian Authority, the bus enters into the Israeli-controlled border crossing. Most of the way, I was treated to the same treatment Palestinians receive. Nothing particularly remarkable, just noticeably more inefficient than the treatment the non-Arab section receives.

Exiting Israeli border security, though, I was transferred to the "tourist" (i.e. non-Arab) bus. My luggage was still with the Palestinian luggage, but I was promised everything would be fine. In a word, it wasn't.

Palestinians, before leaving the Israeli side of the Jordan River, identify their bags and move them to another bus, which meets them after they cross through Jordanian security. Since I was on the "tourist" bus, I ended up in Jordan with my bags back in the West Bank. Five hours later, let's just say I was happy to see my bags again.

Bureacracy's fun, ain't it?

Sunday, November 20, 2005

Historical Archive

Note: This morning, I was invited to preach in the Anglican Church by Fr. Fadi. I followed up in the afternoon with a lecture on both the PCUSA's corporate engagement process and a brief introduction to "Christian Zionism." I preached in English with Arabic translation, but in the afternoon I tried my hand at Arabic - with mixed results. A bit too technical, I fear, for my level of vocabulary.

Note: This morning, I was invited to preach in the Anglican Church by Fr. Fadi. I followed up in the afternoon with a lecture on both the PCUSA's corporate engagement process and a brief introduction to "Christian Zionism." I preached in English with Arabic translation, but in the afternoon I tried my hand at Arabic - with mixed results. A bit too technical, I fear, for my level of vocabulary.My last day in Zababdeh. While I didn't get to see everyone I wanted, I certainly saw many people. I do hope to come back periodically to visit, which eases some of the pressure.

In the evening, I visited with the new Mennonite Central Committee volunteers living here and teaching English at the school. Before coming, they had done a Google search for Zababdeh, finding our website. Before arriving, they had worked their way through the first year and a half of our daily journal archives. It appears we were a bit guarded about our early frustrations and stresses of our time in Zababdeh, which gave them some pause that what they were facing was somehow unusual. I assured them that, in fact, our first year was quite difficult for a number of reasons. Perhaps a re-write is in order?

It is comforting to know that our dedicated work of writing has become an accessible archive - both for our experiences and for the times that we and the people of Zababdeh faced.

Saturday, November 19, 2005

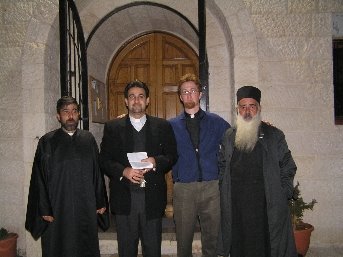

The Three Brothers

Note: I spent much of the day with the Diab family. Fr. Firas (Melkite) and Fr. Fadi (Anglican) are brothers, serving two of the congregations here. We watched our film being broadcast on SAT-7, which today focused on Fr. Firas’ ministry. The children were especially delighted to see themselves on TV.

Note: I spent much of the day with the Diab family. Fr. Firas (Melkite) and Fr. Fadi (Anglican) are brothers, serving two of the congregations here. We watched our film being broadcast on SAT-7, which today focused on Fr. Firas’ ministry. The children were especially delighted to see themselves on TV.This whole trip has been far more intense than I had expected. From the varying perspectives I’ve heard to the suffering I’ve witnessed, it has been gut-wrenching. Today was particularly so, sitting down with some dear friends – both from Zababdeh and from the local Arab-American University of Jenin – to get their take on the current state of things. I also asked them, in particular, to this question: what it is that the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) can be doing to respond?

Essentially, Palestinian society is facing three major problems. The Israeli Occupation is still the primary obstacle, and the chaos it creates in Palestinian society has deep repercussions. But is far from the only problem. Islamic fundamentalism, represented by the likes of Hamas and Islamic Jihad, is distressing for those seeking the modernization of Palestinian society. Meanwhile, the Palestinian Authority (run by the Fatah Party) is beset with deep-seated corruption and independent militias.

In order to understand the problems, as well as the possible solution, one friend suggested that we begin by looking at where these three power brokers do their recruiting.

There is an abundance of large Palestinian families – with eight or nine children – with uneducated parents. Fatah recruiters look for the strongest son, the one who is giving his parents the most trouble. Fatah-related militias are becoming notorious for their extortionism and demands for protection money. Hamas, on the other hand, seeks out the gentlest son, the most reflective one. This has led to Hamas’ rise in political savvy and an improved reputation. The Israelis, looking for collaborators, also go to the same kind of family. They seek out the greediest one, the one who is willing to commit betrayal in exchange for financial recompense. They have made deep inroads into the community.

It may seem an abstract, but there is something to this vision of the metaphorical Palestinian family. It is not too outrageous to imagine these three recruits as brothers. Their situation makes them particularly vulnerable. And so, this family also holds the key to a brighter Palestinian future.

What can the Church, in particular, do?

The answers from my friends aren’t completely clear, but this much is: the advocacy work to end the Occupation could continue; the divestment process and corporate engagement must go forward; our work on economic development in Palestine is needed; our ongoing partnerships in ministry, education, health care, and relief are essential.

But the one question remains: what about the three brothers?

Friday, November 18, 2005

Damaged

On Monday, a Palestinian collaborator called the Israeli Army. Islamic faction activists were holed up in a four-story building in Zababdeh. Within minutes, the Army arrived and shut down a huge section of the town. The streets were filled with soldiers and jeeps. Shooters were positioned on every roof in the area. The students living in the building came out, hands on their heads. "No one is left," they swore to the Army. They didn't believe them, nor the owner of the building. The snipers starting shooting into the windows of the apartment in question. Hours passed. Not one bullet was fired in return.

On Monday, a Palestinian collaborator called the Israeli Army. Islamic faction activists were holed up in a four-story building in Zababdeh. Within minutes, the Army arrived and shut down a huge section of the town. The streets were filled with soldiers and jeeps. Shooters were positioned on every roof in the area. The students living in the building came out, hands on their heads. "No one is left," they swore to the Army. They didn't believe them, nor the owner of the building. The snipers starting shooting into the windows of the apartment in question. Hours passed. Not one bullet was fired in return.Fearing a booby trap, the Army brought a Caterpillar D9 Bulldozer. They began to destroy the building, threatening to level it to rubble. The sides of the building looked like Beirut in the 1980s. The bulldozer ripped off much of the building's facade, including two balconies. Explosives blew off the iron doors. With the intervention of church leaders in town, finally, the Army backed off. They sent in the K-9s. In the end, no one was in the building.

The building belongs to Fr. Toma, the Greek Orthodox priest. His son, an engineer, had saved for eight years working abroad. This was to be his home, his nest egg, the sum of his savings. The damage to the building, from the external to the infrastructure (electricity, sewage system, etc.), is so extensive he will need to save up another four years.

The building belongs to Fr. Toma, the Greek Orthodox priest. His son, an engineer, had saved for eight years working abroad. This was to be his home, his nest egg, the sum of his savings. The damage to the building, from the external to the infrastructure (electricity, sewage system, etc.), is so extensive he will need to save up another four years.This place, this whole land, is damaged. From the factions that hide in other people's property to the Army which destroys it with flimsy evidence, the damage runs deep. It will take years to fix.

Thursday, November 17, 2005

Phase Three: Faded

Walking down the street, I saw a faded picture of a friend of mine on the wall of a building. When I was living here, the only time that I saw such pictures was when someone had become a shaheed - a martyr. Naturally, I assumed this was the case. Then another friend of mine, on another wall: another martyr. Then another, and yet another. I began to wonder what had happened to this town since I left it!

Walking down the street, I saw a faded picture of a friend of mine on the wall of a building. When I was living here, the only time that I saw such pictures was when someone had become a shaheed - a martyr. Naturally, I assumed this was the case. Then another friend of mine, on another wall: another martyr. Then another, and yet another. I began to wonder what had happened to this town since I left it!Finally, I saw the picture of the town's former mayor. It was then, finally, that I understood: these were candidates for the municipal elections, people running for the town council.

In some ways, it seems that the cult of martyrdom has given way to the cult of democracy. But if the pictures tell us anything, both are fading quickly.

Wednesday, November 16, 2005

The Technocrats

Today was our last day of meetings on the economic development of Palestine, the first step of many along the road. It was a great day to end on. We were meeting with some of the key decision-makers within Palestinian society based in Ramallah.

Today was our last day of meetings on the economic development of Palestine, the first step of many along the road. It was a great day to end on. We were meeting with some of the key decision-makers within Palestinian society based in Ramallah.When I lived here, from 2000 to 2003, I had the chance to meet and hear from the decision-makers of the previous "generation" (I use the word loosely). But one key thing was always lacking: there was no articulated vision for how to get out of the problems that faced them. There was always the focus on the Occupation, at times the issue of extremism, but never any sense that their people deserved leadership with vision.

This new "generation" of leaders, sometimes referred to as the Technocrats, is different. They are realistic, facing the fact that the Occupation continues. They are keenly aware of the power and the danger of the radical extremists within Palestinian society. And yet, while seeking accountability, they are also clear that there is a need to build civil society in the meantime. Advocacy and diplomacy continue. Economic development moves forward, despite the obstacles. In a word, there is vision.

For me, in a word, there is hope.

Tuesday, November 15, 2005

Old City Stories

My colleague and I went to have dinner with Christian friends living in Jerusalem's Christian quarter. Their home is made in the classic Arab style, its exterior walls three feet thick. They are separated from the Old City's 16th century walls by a narrow alleyway. It may be a cliché, but if these walls could talk...

My colleague and I went to have dinner with Christian friends living in Jerusalem's Christian quarter. Their home is made in the classic Arab style, its exterior walls three feet thick. They are separated from the Old City's 16th century walls by a narrow alleyway. It may be a cliché, but if these walls could talk...Two years ago, right before leaving Palestine, I had visited with them. The Matriarch of the family, now passed away, shared her memory of those days of living on the edge of history. I missed her last night, but I recalled her chilling stories of 1948.

We were living in West Jerusalem. One day, someone knocked at the door of our home. They said, "We're the Haganah [Jewish paramilitary organization, predecessor of the Israeli Army]."

We didn't know who they were. "Come on in," we said.

"You have 48 hours to leave, or else."

"Or else what?"

"Or else we'll kill you."

The family left, their two-week-old baby girl in tow, seeking refuge in Bethlehem. One night, they ducked down in the cab of a truck as bullets flew around them. As the front line receded temporarily, they went back to their house. A Jewish family had already taken possession. They left everything they owned in their home. As the front line progressed, they went to Jordan to live in a tent. After the Armistice, they returned to the Old City to stay.

The family left, their two-week-old baby girl in tow, seeking refuge in Bethlehem. One night, they ducked down in the cab of a truck as bullets flew around them. As the front line receded temporarily, they went back to their house. A Jewish family had already taken possession. They left everything they owned in their home. As the front line progressed, they went to Jordan to live in a tent. After the Armistice, they returned to the Old City to stay.The Matriarch's story was that of a Palestinian refugee. It is one among many in this conflict. But in the world of politics, the issue of Palestinian refugees is too easily cast aside. The story of dispossession is deeply embedded in the Palestinian psyché. It is an integral part of Palestinian identity. For many Palestinians, what happened in 1948 is part of a long narrative of loss that continues until today. It is a deep wound, as substantial as the walls of this beautiful, troubled Old City.

Monday, November 14, 2005

A Slap in the Face

The cover of Ha'aretz, the Israeli daily newspaper, carried a picture of Senator Hilary Clinton on her visit to Israel. The backdrop was a map bearing the title "The Anti-Terror Fence." Blurred in the background was a section of the twenty-five foot high wall surrounding Bethlehem. Senator Clinton spoke of Israel's wonderful efforts to defend itself with minimal disruption to Palestinian life.

The cover of Ha'aretz, the Israeli daily newspaper, carried a picture of Senator Hilary Clinton on her visit to Israel. The backdrop was a map bearing the title "The Anti-Terror Fence." Blurred in the background was a section of the twenty-five foot high wall surrounding Bethlehem. Senator Clinton spoke of Israel's wonderful efforts to defend itself with minimal disruption to Palestinian life.I was two miles away, on the other side of this "fence," meeting with church partners and leaders of civil society. We discussed in great detail and with great nuance the grievous harm the Wall is doing to Palestinian life, as we strategized what could be done with these facts cemented in place.

Fact: 60% of Bethlehem's land is outside of the Wall. If farmers cannot harvest this land for six years, Israel can (and likely will) seize it under the laws instituted during the Ottoman Turkish Empire regarding "absenteeism."

Fact: 60% of Bethlehem's land is outside of the Wall. If farmers cannot harvest this land for six years, Israel can (and likely will) seize it under the laws instituted during the Ottoman Turkish Empire regarding "absenteeism."On Saturday, the Clinton's visited the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, paying their respects to the holy place and, by doing so, honored the indigenous Christian community. Less than forty-eight hours later, Senator Clinton aggressively slapped that same community in the face. Standing just outside of Bethlehem, choosing not to venture into the besieged city, she allowed herself to be used as propaganda. If one is to believe her remarks, the suffering of the Palestinian community is fully and completely its own fault.

I have always stood firmly against the evil - and I don't use the word lightly - of suicide bombing. Most Palestinians believe that the Second Intifada brought them far more harm than good, and I agree with that assessment. I also agree with the Israeli human rights group B'Tselem that Israel has a right to defend itself, and could do so by building a barrier along the internationally-recognized Green Line. However, given the path that the Barrier has taken, I am convinced that Israel is, once again, using security as an excuse. This is Middle Eastern "Manifest Destiny" at its clearest.

I have always stood firmly against the evil - and I don't use the word lightly - of suicide bombing. Most Palestinians believe that the Second Intifada brought them far more harm than good, and I agree with that assessment. I also agree with the Israeli human rights group B'Tselem that Israel has a right to defend itself, and could do so by building a barrier along the internationally-recognized Green Line. However, given the path that the Barrier has taken, I am convinced that Israel is, once again, using security as an excuse. This is Middle Eastern "Manifest Destiny" at its clearest.It's not a good day to be an American.

Sunday, November 13, 2005

Wedding Feast

In the end, I spent the night with dear friends at the Latin Patriarchate Seminary in Beit Jala, particularly Fr. Aktham, the priest with whom Elizabeth and I worked so closely in Zababdeh.

Mass at the Latin Church in Beit Sahour, where the angels appeared to the shepherds (Luke 2), began at 9:30 this morning. I took a seat in the second pew. During the first hymn, Fr. Faisal sent word to me: "Please join us in the chancel." I did, taking my seat beside several priests and a swarm of seminarians. Fr. Faisal introduced me to his parish, highlighting our time in Zababdeh with the Latin Church and our documentary film. Fr. Majdi added a word about the Presbyterian Church, reminding the congregation that we had begun corporate engagement in Israel/Palestine. After worship, members of the congregation greeted me: "Thank you for all that you are doing." "May God strengthen you!" "We are extremely grateful to the Presbyterian Church."

Mass at the Latin Church in Beit Sahour, where the angels appeared to the shepherds (Luke 2), began at 9:30 this morning. I took a seat in the second pew. During the first hymn, Fr. Faisal sent word to me: "Please join us in the chancel." I did, taking my seat beside several priests and a swarm of seminarians. Fr. Faisal introduced me to his parish, highlighting our time in Zababdeh with the Latin Church and our documentary film. Fr. Majdi added a word about the Presbyterian Church, reminding the congregation that we had begun corporate engagement in Israel/Palestine. After worship, members of the congregation greeted me: "Thank you for all that you are doing." "May God strengthen you!" "We are extremely grateful to the Presbyterian Church."I know, in my heart of hearts, that what the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) is doing along these lines is right. In the States, we have received grief for this witness. So to hear this word from brothers and sisters in Christ is deeply encouraging.

My ecumenical experience in Palestine has been nothing but welcoming. And yet, I try not to assume a place of honor for myself. To paraphrase the parable, I don't assume that I have a seat at the head banquet table (Luke 14). But when invited, I come with joy. Today, I joined the banquet with gratitude. And I leave Bethlehem with a heart full for both the hardships and the witness of these dear brothers and sisters. May God strengthen them.

Saturday, November 12, 2005

No god but God

Yet the deadliest of the attacks hit the heart of a Muslim wedding party. The next day, at the same hotel a Christian wedding party took place. It seems to me that this points to a struggle not between East and West, but within Islam itself. Scholars like Reza Aslan (e.g. his book No god but God) and Mohammad Sammak see the dividing lines between those seeking radicalization and those seeking modernization. My own experience with the Palestinian Islamic community underscores this analysis.

Half of those killed in the wedding party were Palestinians from Jenin. In Jerusalem, all news seems to be local news.

I did take the opportunity yesterday to walk the ramparts of the Old City walls, a walk that was closed during my time here "due to security reasons." It was an amazing walk that takes you half way around the city. On the left, you see the life outside the walls (and the architectural beauty that the walls themselves are). On the right, you see life within the Old City: houses, churches, playgrounds, settlements, schools, workshops. It is a helpful reminder that Jerusalem is not just a symbol, not just an idea. It is, first and foremost, a place where people live. It is for the sake of these people that we should seek peace.

I did take the opportunity yesterday to walk the ramparts of the Old City walls, a walk that was closed during my time here "due to security reasons." It was an amazing walk that takes you half way around the city. On the left, you see the life outside the walls (and the architectural beauty that the walls themselves are). On the right, you see life within the Old City: houses, churches, playgrounds, settlements, schools, workshops. It is a helpful reminder that Jerusalem is not just a symbol, not just an idea. It is, first and foremost, a place where people live. It is for the sake of these people that we should seek peace.Friday, November 11, 2005

Phase Two

Phase Two is directly related to my work with the General Assembly staff, following up on a General Assembly resolution establishing an Israel/Palestine Mission Network and calling for an economic feasibility study of the Palestinian economy. Therefore, I'll be spending the next few days with several colleagues meeting with church partners and economists to get their analysis on the economic situation in Gaza, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem. It will be much slower than our time over the last ten days, hopefully allowing me time to reconnect with friends in and around Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Ramallah.

Thursday, November 10, 2005

Giving Up Slowly

"What are the Jabers made of?" I asked Rich Meyer, from Christian Peacemaker Teams, as he guided us through Hebron yesterday. The Jaber family have been harrassed, threatened, and endangered at the hands of the most extreme settlers near their home in the Beqa'a Valley. Homes have been torched, family members attacked, all in an effort to frighten them off their land. I tried to figure out what it was that kept them from throwing in the towel. Rich replied, "I think it's called 'giving up as slowly as possible.'"

"What are the Jabers made of?" I asked Rich Meyer, from Christian Peacemaker Teams, as he guided us through Hebron yesterday. The Jaber family have been harrassed, threatened, and endangered at the hands of the most extreme settlers near their home in the Beqa'a Valley. Homes have been torched, family members attacked, all in an effort to frighten them off their land. I tried to figure out what it was that kept them from throwing in the towel. Rich replied, "I think it's called 'giving up as slowly as possible.'" I heard the echoes of these words as I walked the grounds of Daoud Nassar's family land near the village of Nahallin. One look at the hilltops around reveals how tentative his hold on this piece of rocky ground is. In every direction, Israeli settlements loom. Fingers of these settlements reach out along the crest of the hill to connect with the next one. Daoud is surrounded.

I heard the echoes of these words as I walked the grounds of Daoud Nassar's family land near the village of Nahallin. One look at the hilltops around reveals how tentative his hold on this piece of rocky ground is. In every direction, Israeli settlements loom. Fingers of these settlements reach out along the crest of the hill to connect with the next one. Daoud is surrounded.Settlers have come to his land many times. They have tried to build a road onto it. They have threatened Daoud's mother at gunpoint. They have uprooted 250 olive trees. And when that failed, they tried to bribe him. "It's a blank check. Name your price. We'll help you leave."

The legal battle has been a protracted one as well, now nearly fifteen years old. Daoud has the right documents, dating from 1916 when his grandfather registered the land under the Ottoman Empire. He has provided a series of surveys, from as long ago as the British Mandate and as recently as 2001. The court has ruled them all insufficient and has required him to hire an Israeli surveyor at a cost of $70,000. And on it goes.

In an effort to defray the prohibitive legal costs, as well as to raise awareness about the issue of land confiscation in general, Daoud has established "The Tent of Nations." Internationals come to this hilltop to lend a hand (we planted a few onions), learn the issues, raise awareness, and take part in a variety of programs.

I am deeply impressed by Daoud's courage. I hope it's not a case of "giving up as slowly as possible." Daoud has succeeded thus far where so many others have failed. Our bus driver jokes that the Palestinian state will have to be established on this 100 acres. Looking around the dust of further settlement all around us, it's hard to imagine otherwise.

I am deeply impressed by Daoud's courage. I hope it's not a case of "giving up as slowly as possible." Daoud has succeeded thus far where so many others have failed. Our bus driver jokes that the Palestinian state will have to be established on this 100 acres. Looking around the dust of further settlement all around us, it's hard to imagine otherwise.If you want further information, you can visit the Tent of Nations webpage. Daoud's pastor, the Rev Dr. Mitri Raheb, also wrote about the situation in his book I Am a Palestinian Christian (in the chapter entitled "Daher's Vineyard.")

Wednesday, November 09, 2005

Intermission

Tuesday, November 08, 2005

Untitled

In the spring of 1991, I was a college student wandering around Europe. Of the many places I knew I had to visit were the Nazi death camps of Dachau and Auschwitz. It was like an anti-pilgrimage: as Jerusalem’s holy sites can inspire deep upwellings of faith and joy, these bring dread and horror. It was as though the stones of the ground on which we walked were haunted with the dead. In Auschwitz, I was horrified by how close the Camp was to the town. Surely these folks knew what was happening! And as always, the scale of the mass slaughter boggles the mind. Polish Jews, who made up ten percent of their nation prior to World War II, were nearly eradicated, making up half of the six million Jewish victims .

Everything in the context of Israel/Palestine is infused with the political. One cannot visit Yad v’Shem, the Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem, without seeing it through the lens of the current conflict. But as much as extremists on either side wish to identify their enemy with the Nazis, the comparison is unhelpful at best; at worst, it dances on the graves of the victims of genocide. As a Christian who shares complicity for evils committed by my co-religionists, I begin with my own confession for the sins of the Church (for a particularly haunting historical list, read Kathleen Kern’s We Are the Pharisees). Their perniciousness, to me, lies in the fact that they are evil committed in the name of the God of grace. For this reason, and for the fact that I am neither an Israeli nor a Jew, I hesitate to describe the sentiments of Israelis towards these events. Rather, I primarily seek to listen; this is why I came on this trip and why I have treasured the opportunity to spend hours in conversation with the Jewish members of our delegation in an effort to see this all through their eyes. However, today’s experiences make me need to do more than listen; I need to comment, to try to sort out my thoughts and feelings.

Everything in the context of Israel/Palestine is infused with the political. One cannot visit Yad v’Shem, the Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem, without seeing it through the lens of the current conflict. But as much as extremists on either side wish to identify their enemy with the Nazis, the comparison is unhelpful at best; at worst, it dances on the graves of the victims of genocide. As a Christian who shares complicity for evils committed by my co-religionists, I begin with my own confession for the sins of the Church (for a particularly haunting historical list, read Kathleen Kern’s We Are the Pharisees). Their perniciousness, to me, lies in the fact that they are evil committed in the name of the God of grace. For this reason, and for the fact that I am neither an Israeli nor a Jew, I hesitate to describe the sentiments of Israelis towards these events. Rather, I primarily seek to listen; this is why I came on this trip and why I have treasured the opportunity to spend hours in conversation with the Jewish members of our delegation in an effort to see this all through their eyes. However, today’s experiences make me need to do more than listen; I need to comment, to try to sort out my thoughts and feelings. For most Israelis, the events of the Holocaust are directly tied to Zionism and the establishment of Israel as a state. This simple point is communicated even in the architecture at Yad v’Shem: the exit of one exhibit hall opens out onto a magnificent vista of villages along the hillsides West of Jerusalem; the arch above the exit to the complex bears an inscription from the prophet Ezekiel, “I will set you down upon your own soil.” From the political, moral, and religious points of view, the Holocaust and Zionism have been intertwined.

For most Israelis, the events of the Holocaust are directly tied to Zionism and the establishment of Israel as a state. This simple point is communicated even in the architecture at Yad v’Shem: the exit of one exhibit hall opens out onto a magnificent vista of villages along the hillsides West of Jerusalem; the arch above the exit to the complex bears an inscription from the prophet Ezekiel, “I will set you down upon your own soil.” From the political, moral, and religious points of view, the Holocaust and Zionism have been intertwined.The Holocaust shapes the Israeli psyche, and seems to motivate folks from the left to the right, even those who have no personal link to European Jewry. The phrase “Never again” is common. To some, it means no injustice anywhere to anyone; to others, it means the Jewish people are always at risk; to many, it means some combination of the two. As we’ve moved among the Jewish community of Israel, the Holocaust is a recurring theme. Each of the Israeli peace activists with whom we’ve spoken begins their story with it. And each of our meetings today was visited by its ghosts.

We left Yad v’Shem for Ma’ale Adumim, to meet with Shimon Ansbacher, a German Holocaust survivor, one of the founders of this expansive West Bank settlement. He was cordial and hospitable, welcoming us in one of the board rooms of the City Hall. While the residents of Ma’ale Adumim have a reputation as non-ideological settlers, it was clear this was not the case of Mr. Ansbacher. The more he spoke, the more uneasy I became. All eighteen of his grandchildren live in among the most religiously extreme settlements. Five of them went to Gaza to resist the disengagement, the fact of which he is extremely proud. Rabbi Levinger, one of the founders of the extremist Hebron settlements, is his hero. He opposes a two-state solution as well as the Wall (which he calls “an idiocy”) – not because of its human cost, financial cost, or failures to stop attacks, but “because this is Eretz-Yisrael (the land of Israel) as promised to Avraham Avinu (our ancestor Abraham).” Several versions of radical, racist ideologies filtered through his thoughts: Palestinians=Philistines; Jordan is the Palestinian State; Arab population growth is a result of Islamic polygamy; Islam is a “barrel of dynamite.” Arabs would be welcome to live “equally” in his vision of Eretz-Yisrael, but without the right to vote, serve in the Knesset, or have any say in their affairs. It was, to me, a dark version of double-speak, where oppression is peace and triumphalism is faith.

We left Yad v’Shem for Ma’ale Adumim, to meet with Shimon Ansbacher, a German Holocaust survivor, one of the founders of this expansive West Bank settlement. He was cordial and hospitable, welcoming us in one of the board rooms of the City Hall. While the residents of Ma’ale Adumim have a reputation as non-ideological settlers, it was clear this was not the case of Mr. Ansbacher. The more he spoke, the more uneasy I became. All eighteen of his grandchildren live in among the most religiously extreme settlements. Five of them went to Gaza to resist the disengagement, the fact of which he is extremely proud. Rabbi Levinger, one of the founders of the extremist Hebron settlements, is his hero. He opposes a two-state solution as well as the Wall (which he calls “an idiocy”) – not because of its human cost, financial cost, or failures to stop attacks, but “because this is Eretz-Yisrael (the land of Israel) as promised to Avraham Avinu (our ancestor Abraham).” Several versions of radical, racist ideologies filtered through his thoughts: Palestinians=Philistines; Jordan is the Palestinian State; Arab population growth is a result of Islamic polygamy; Islam is a “barrel of dynamite.” Arabs would be welcome to live “equally” in his vision of Eretz-Yisrael, but without the right to vote, serve in the Knesset, or have any say in their affairs. It was, to me, a dark version of double-speak, where oppression is peace and triumphalism is faith. Fortunately, we had one more meeting to round out the day. Paz and Keren are studying political science at Hebrew University. Keren’s time in the army overlapped with my time in Zababdeh – in fact, Zababdeh was in the region her battalion patrolled. Our experiences of those two intersecting years diverge wildly – her description of the battle in Jenin Refugee Camp centers on the killing of thirteen soldiers, mine with the leveling of homes and the staggering civilian death toll. She despairs over the poverty in which Palestinians live, but lives in fear from suicide attacks which have targeted her town. I decry those same bombings, but believe that the best prevention is to improve Palestinian life. She is afraid to go into East Jerusalem at night, I get nervous at the sight of an Israeli military jeep.

Fortunately, we had one more meeting to round out the day. Paz and Keren are studying political science at Hebrew University. Keren’s time in the army overlapped with my time in Zababdeh – in fact, Zababdeh was in the region her battalion patrolled. Our experiences of those two intersecting years diverge wildly – her description of the battle in Jenin Refugee Camp centers on the killing of thirteen soldiers, mine with the leveling of homes and the staggering civilian death toll. She despairs over the poverty in which Palestinians live, but lives in fear from suicide attacks which have targeted her town. I decry those same bombings, but believe that the best prevention is to improve Palestinian life. She is afraid to go into East Jerusalem at night, I get nervous at the sight of an Israeli military jeep.I still end today more in despair than hope. And yet, I am transformed by this final meeting. I have invited Keren to get together while I am in Jerusalem after the delegation disperses, and she accepts. I expect to write more about that meeting if/when it happens. What am I hoping for? I’m not really sure to be honest, but something about it seems right. Perhaps we would compare notes and stories from our time in the Jenin region. Maybe we can challenge and test each other’s assumptions about the conflict as a whole. Then again, perhaps there’s nothing to be gained from this at all. But if there’s no risk, despair wins. And in the shadow of Auschwitz and Yad v’Shem, I must plant seeds of hope.

Monday, November 07, 2005

Pressure Cooker

"Do you cry when you see a Palestinian child killed?" The question is posed to us by a young woman at Birzeit University. It's a question that speaks volumes. When I was here two years ago, nearly all of the Palestinians I met would quickly differentiate between American politics and American people. "If you're here," the reasoning went, "you must not be supportive of American policy." The line seems to be blurring more and more, though. We are the power behind the throne, the financial prop that supports Israel - for good and for ill. The Occupation of Iraq is linked to the Occupation of Palestine. I feel it the whole time we are on campus.

"Do you cry when you see a Palestinian child killed?" The question is posed to us by a young woman at Birzeit University. It's a question that speaks volumes. When I was here two years ago, nearly all of the Palestinians I met would quickly differentiate between American politics and American people. "If you're here," the reasoning went, "you must not be supportive of American policy." The line seems to be blurring more and more, though. We are the power behind the throne, the financial prop that supports Israel - for good and for ill. The Occupation of Iraq is linked to the Occupation of Palestine. I feel it the whole time we are on campus.Do we cry? What kind of question is that? Of course we do. Only a monster wouldn't cry at the death of a child. Or is it that they think we're monsters? "It's very nice that you cry," one professor remarks. "But you are still complicit, because it is your taxes which are supporting this Occupation." It's a sharp comment - more direct than I'm used to from Palestinians. Something has changed - or has it?

Everywhere we go, we see the hardships. West Bank cities have been closed down to one entrance and exit, and access to the outside world is limited to those who have the necessary permits. The Wall is an oppressive reality, present on every hillside. Poverty is rampant. Unemployment is skyrocketing. While there is talk of peace, there seems to be little progress towards peace. It seems that little changed in the last two years.

Everywhere we go, we see the hardships. West Bank cities have been closed down to one entrance and exit, and access to the outside world is limited to those who have the necessary permits. The Wall is an oppressive reality, present on every hillside. Poverty is rampant. Unemployment is skyrocketing. While there is talk of peace, there seems to be little progress towards peace. It seems that little changed in the last two years.Except for one thing: the checkpoint lines are shorter - much shorter. It seems that resignation has set in, that Palestinians have resigned themselves to make it as much as they can in their open air prisons. Where there is resignation, there is frustration. And where there is frustration, the pressure builds. It is palpable.

This oppression must stop. No one should have to live like this. It is unconscionable. If not for the sake of the Palestinians, then for the sake of the Israelis. If not for their sake, then for the sake of the Americans. If not for our sake, then for the sake of morality itself.

This oppression must stop. No one should have to live like this. It is unconscionable. If not for the sake of the Palestinians, then for the sake of the Israelis. If not for their sake, then for the sake of the Americans. If not for our sake, then for the sake of morality itself.Sunday, November 06, 2005

Grandmas and Rappers

Note: This morning, we worshiped at the Basilica of the Annunciation in Nazareth.

Note: This morning, we worshiped at the Basilica of the Annunciation in Nazareth.“Can you guess where we are?” Our guide Tamer asked us, pointing at the official map of Lod. “It’s the blank spot in the corner. According to the government, we don’t even exist.” We stood in the empty parking lot near the Mahatta area of Lod (called Lid in Arabic), a mixed city where Israeli Jews and Palestinians with Israeli citizenship live. But it is clearly a segregated city. Mahatta, home to 9000 Palestinians, doesn’t exist. It isn’t on the map. It is squeezed on all sides by the railroad, the highway, and Jewish-only neighborhoods. We literally cross the tracks – eight commuter rail lines that bisect the area’s only entrance – and enter Mahatta. In the five minutes that we stand there, trains shoot by, closing the road for four of those minutes.

This is our second day among the so-called “Arab Israelis.” In meetings with Ittijah (Union of the Arab Community Based Organisations) and Ma’an (Workers Advice Center), we learn profound statistics. 10% of Arab Israelis live in unrecognized villages, towns which don’t appear on official maps and thus receive no services – electricity, water, sewage, education. 25% are internally displaced, having fled their homes in 1948 but ended up within the borders of Israel, and yet not allowed to recoup their properties. “We are a community at risk,” Ittijah’s Director Ameer Makhoul tells us. These words don’t fully sink in until we cross over into Mahatta the next day.

On the other side of the railroad is pure squalor. Thirty percent of the Palestinian population in Lid isn’t connected to the sewage system – in Mahatta, it seems to be higher. Tamer Nafar is a local hero, as we see from the crowds of kids who follow us and shout his name. He is a hip-hop artist, quoting socially conscious rappers like Tupac and Chuck D to underscore that this is life in the Palestinian ghettoes of Israel. He looks the part, in baggy jeans, wool cap, and oversized hooded sweatshirt. His raps are punctuated with Arabic cultural references – musicians like ‘Abd al-Halim and Egyptian films are his poetic landscape. He has also become an activist, working with organizations like Shatil and Coalition of Women for Peace.

On the other side of the railroad is pure squalor. Thirty percent of the Palestinian population in Lid isn’t connected to the sewage system – in Mahatta, it seems to be higher. Tamer Nafar is a local hero, as we see from the crowds of kids who follow us and shout his name. He is a hip-hop artist, quoting socially conscious rappers like Tupac and Chuck D to underscore that this is life in the Palestinian ghettoes of Israel. He looks the part, in baggy jeans, wool cap, and oversized hooded sweatshirt. His raps are punctuated with Arabic cultural references – musicians like ‘Abd al-Halim and Egyptian films are his poetic landscape. He has also become an activist, working with organizations like Shatil and Coalition of Women for Peace.The whole scene is one of ironic contrasts. The trains carry middle and upper class suburbanites past. Nearby Ben Gurion airport, built on land belonging to the Palestinian residents of Lid, is “the face of Israel,” Tamer tells us. “Not this place.” New high-rises for Russian Jewish immigrants can be seen over the piles of Mahatta’s uncollected garbage. As for the mounting unsolved crimes in Mahatta, Tamer references Israel’s concern about the Palestinian birth rate in Israel. “For them, it’s not a problem if I die. But if I’m born, that’s a problem.”

One final contrast for the day was our journey from the poverty of Lid to the suburbs of Tel Aviv. Our dinner hosts were Israeli grandmothers Dorothy Naor and Ruth Hiller of New Profile. Now in its seventh year, the group works to address the pervasive militarism in Israeli society. They offer us several examples. One Israeli mother, at the funeral of her soldier son, said, “Today, I have become an Israeli.” When a baby boy is born, his parents are complimented: “The next Chief of Staff,” their friends tell them. “So even if the Occupation ends,” Ruth tells us, “the militarism is still there.”

One final contrast for the day was our journey from the poverty of Lid to the suburbs of Tel Aviv. Our dinner hosts were Israeli grandmothers Dorothy Naor and Ruth Hiller of New Profile. Now in its seventh year, the group works to address the pervasive militarism in Israeli society. They offer us several examples. One Israeli mother, at the funeral of her soldier son, said, “Today, I have become an Israeli.” When a baby boy is born, his parents are complimented: “The next Chief of Staff,” their friends tell them. “So even if the Occupation ends,” Ruth tells us, “the militarism is still there.”From the last two days, it is clear that the violence of Israel/Palestine goes far beyond the violence of Occupation and Terrorism. It is a systemic, dehumanizing violence. There is much reason for despair. But between the rappers and the grandmothers, there might just be hope.

Saturday, November 05, 2005

Whitewash

After seeing the Wall for several days from the Palestinian side, our drive up to the Galilee took us past the Wall from the Israeli side. Alongside one highway, it is colorfully painted with arches, through which one can see stylized views of Israeli homes and communities. Alongside another, the ground is landscaped so that a gentle hill leads up to the top of the Wall, giving it the appearance of being only two or three feet high (rather than the twenty-five foot monstrosity that you see from the Palestinian side). In other words, it is very easy for the average Israeli to believe that there is no Wall, or that it isn't that bad.

After seeing the Wall for several days from the Palestinian side, our drive up to the Galilee took us past the Wall from the Israeli side. Alongside one highway, it is colorfully painted with arches, through which one can see stylized views of Israeli homes and communities. Alongside another, the ground is landscaped so that a gentle hill leads up to the top of the Wall, giving it the appearance of being only two or three feet high (rather than the twenty-five foot monstrosity that you see from the Palestinian side). In other words, it is very easy for the average Israeli to believe that there is no Wall, or that it isn't that bad. The Wall has been built. It is being extended. It offers no peace for Israelis outside it, and no justice for Palestinians trapped within it. And the government of Israel is smearing it with whitewash, covering it with frescoes, hiding its inhumanity. I pray for the day that we will be able to say, "The Wall is no more." May it come soon.

The Wall has been built. It is being extended. It offers no peace for Israelis outside it, and no justice for Palestinians trapped within it. And the government of Israel is smearing it with whitewash, covering it with frescoes, hiding its inhumanity. I pray for the day that we will be able to say, "The Wall is no more." May it come soon.Friday, November 04, 2005

Shabbat Shalom

Note: Among our busy day was a very moving visit with Gila Svirsky of the Coalition of Women for Peace. More information about their important outreach can be found at their website. We also joined the Israeli Women in Black, part of the Coalition, for their silent Friday vigil against the Occupation. The Jerusalem traffic greeted us with a mixture of thumbs up and middle fingers.

Note: Among our busy day was a very moving visit with Gila Svirsky of the Coalition of Women for Peace. More information about their important outreach can be found at their website. We also joined the Israeli Women in Black, part of the Coalition, for their silent Friday vigil against the Occupation. The Jerusalem traffic greeted us with a mixture of thumbs up and middle fingers.“It’s not just today,” Ali said to Nurit. “In 1968, my brother and I visited Haifa. The soldiers put us in jail for the whole day, just for being Arabs. Don’t think that the Occupation just began in 2000.” Nurit Steinfeld works diligently for Machsom Watch, an Israeli organization that monitors the treatment of Palestinians at Israeli checkpoints. Their work has highlighted cases of abuse and has caused the Israeli Army to seek their cooperation. Nurit was at an Israeli DCO (District Coordinating Office) recently when she met Ali, who was refused a two-day pass to Jerusalem for his wife’s heart surgery. Nurit agreed to take the two of them back home from the hospital. Since then, she has heard many of his stories of humiliation at the hands of the Israelis:

- During the first Intifada, Ali was a school principal. On his way to work one morning, soldiers grabbed him and forced him to paint over some Palestinian nationalist graffiti nearby. Having no paint, he got on his knees and made mud to cover the wall with his hands. He arrived late to work, where his Israeli military supervisor told him he invented the harassment story.

- When Ali went to Jerusalem for an angioplasty, the DCO gave him a one-day pass and told him a letter from his doctor would be sufficient to replace his expired pass on the second day. When he arrived at the checkpoint to go back home, the soldier forced him to crouch on the side of the road for four hours with his hands on his head – all of this one day after his surgery.

- One month ago, Israeli soldiers attacked his house at 2:00 am. They hauled the family outside and searched the premises. They then arrested Ali’s oldest son, a college student at Jerusalem Open University. Ali attended the trial and heard the judge say, “There is no evidence against this man.” However, under the Israeli process of Administrative Detention, it is sufficient enough for the prosecution to say that evidence is being withheld for reasons of security. Ali’s son is still in jail, and Ali can pay the bail of $2,400 to get him released until the appeal.

All of this, and Ali still welcomes Nurit, a Jewish Israeli, in front of his house with exquisite Hebrew. His shy young daughters serve twelve total strangers cups of juice as we listen with rapt attention to his every word. “Israel has always been a symbol of hope for me,” Nurit, the child of Slovak Holocaust survivors, tells us. “But hearing Ali’s stories, stories that every Palestinian shares, makes me see the cost that my hope means.”

All of this, and Ali still welcomes Nurit, a Jewish Israeli, in front of his house with exquisite Hebrew. His shy young daughters serve twelve total strangers cups of juice as we listen with rapt attention to his every word. “Israel has always been a symbol of hope for me,” Nurit, the child of Slovak Holocaust survivors, tells us. “But hearing Ali’s stories, stories that every Palestinian shares, makes me see the cost that my hope means.”

Several hours later, we met with Rabbi Jim Lebo prior to tonight’s Qabbalat Shabbat service. Rabbi Lebo gave us some background on the place his American Conservative Synagogue has in the Israeli religious spectrum – somewhere between the 20% secular and 20% ultra-Orthodox society. His was the least political of the lectures we have had, but it was far from being apolitical. “From the year 73 of the common era,” he tells us, “Jews have yearned to return to this land. And as the sage has said, ‘If one never gives up the claim to a lost object, he or she is entitled to possession of it.’” I pondered how the arguments we often use in our defense are ones that could easily be turned on us. I also couldn’t help but think of how the residents of Dheisheh Refugee Camp might welcome the Rabbi’s wisdom to plead their case.

“We welcome you in our midst. We bless you as you work for peace. We hope that you will bless us.” These words greeted us as we joined the Friday night service. The energy from the young congregation was infectious, and I stumbled along with the Hebrew as we clapped and sang psalms and praises to Adonai. The text was replete with redemptive phrases that undercut any and all who would use power to get their way: destroyed cities being rebuilt, captives and prisoners finding release, the oppressed seeing justice and restoration. This was not a leftist congregation by any stretch. Many of the young people sitting around us will likely enter the military. As our conversation with Rabbi Lebo indicated, there would be significant points of political disagreement. And yet, there in worship, I was profoundly moved. These Israelis, who sing for peace. Do they really know what makes for peace? Do I really know what makes for peace? Do any of us really know what makes for peace?

When I speak of my own desire for peace on behalf of Israelis and Palestinians, these people will be added to the faces I see. Blessed are you, O Lord, our God. And blessed are all the children of Adam. Shabbat Shalom.

Thursday, November 03, 2005

Guevara and Gandhi

The first thing you notice about Jihad is that he looks just like his necklace. His hair is full and thick, his beard scruffy, his face an intense gaze. “They call me Che,” he tells us, as he fingers the Guevara medallion around his neck. “Che” takes us on a tour of Bethlehem’s Dheisheh Refugee Camp, one square kilometer which 11,000 Palestinians call home. Refugees and their descendants from the West Jerusalem corridor, Dheisheh’s residents (like their counterparts in the Territories and throughout the Middle East) were dispossessed by the establishment of Israel, alternately ignored or manipulated by the Arab world, overlooked by the Palestinian Authority, and largely dismissed by the international community. Their narrative, as “Che” shared with us, is strong and hard to swallow. For Palestinians, the dispossession of 1948 is central to their identity, and any effort to understand them must hear such voices.

The first thing you notice about Jihad is that he looks just like his necklace. His hair is full and thick, his beard scruffy, his face an intense gaze. “They call me Che,” he tells us, as he fingers the Guevara medallion around his neck. “Che” takes us on a tour of Bethlehem’s Dheisheh Refugee Camp, one square kilometer which 11,000 Palestinians call home. Refugees and their descendants from the West Jerusalem corridor, Dheisheh’s residents (like their counterparts in the Territories and throughout the Middle East) were dispossessed by the establishment of Israel, alternately ignored or manipulated by the Arab world, overlooked by the Palestinian Authority, and largely dismissed by the international community. Their narrative, as “Che” shared with us, is strong and hard to swallow. For Palestinians, the dispossession of 1948 is central to their identity, and any effort to understand them must hear such voices.  Dheisheh’s Ibdaa Center, our host, works overtime to make sure that the world has the chance to listen. They have preserved pictures of their community from 1948 on, and the entrance to the Center is framed by the revolving cage which was the camp’s only entrance/exit from 1985 to 1995, the Israeli army controlling their coming and going and surrounding them with a tall fence. “Che” himself had little time for communal self-critique (e.g. defining all Palestinian resistance as a purely defensive act). Unfortunately, among Palestinians and Israelis, as among Americans or Iraqis, such humility is all-too absent.

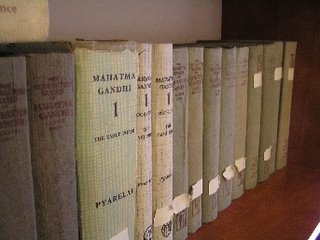

Dheisheh’s Ibdaa Center, our host, works overtime to make sure that the world has the chance to listen. They have preserved pictures of their community from 1948 on, and the entrance to the Center is framed by the revolving cage which was the camp’s only entrance/exit from 1985 to 1995, the Israeli army controlling their coming and going and surrounding them with a tall fence. “Che” himself had little time for communal self-critique (e.g. defining all Palestinian resistance as a purely defensive act). Unfortunately, among Palestinians and Israelis, as among Americans or Iraqis, such humility is all-too absent. A few miles away, the offices of Holy Land Trust are lined with The Complete Works of Mahatma Gandhi. Hosam Jubran, one of the leaders of this Muslim-Christian organization, outlined the various programs of HLT. Primary among them is their nonviolence awareness and training. Hosam spends much of his time traveling the West Bank, educating young people about the religious and national histories of non-violent resistance which Palestinian Christians and Muslims share. Nationally, the image of non-violence is that of passivity, acquiescence. But when Hosam explains that Palestinians have always had a history of non-violent resistance – tax revolts, worker strikes, etc. – opinions begin to shift. “The success of violent resistance as a strategy is a valid debate,” he tells us. “But there is no question about the success of non-violent resistance. Our goal is not simply to end the Occupation, but to build civil society afterwards.” In other words, a culture of non-violence spells a brighter future. Hosam sees non-violent resistance growing, highlighting the active creativity of towns like Bil’in and Budros. “Our work now is to connect the dots. We are one to two years away from a serious national non-violent movement.”

A few miles away, the offices of Holy Land Trust are lined with The Complete Works of Mahatma Gandhi. Hosam Jubran, one of the leaders of this Muslim-Christian organization, outlined the various programs of HLT. Primary among them is their nonviolence awareness and training. Hosam spends much of his time traveling the West Bank, educating young people about the religious and national histories of non-violent resistance which Palestinian Christians and Muslims share. Nationally, the image of non-violence is that of passivity, acquiescence. But when Hosam explains that Palestinians have always had a history of non-violent resistance – tax revolts, worker strikes, etc. – opinions begin to shift. “The success of violent resistance as a strategy is a valid debate,” he tells us. “But there is no question about the success of non-violent resistance. Our goal is not simply to end the Occupation, but to build civil society afterwards.” In other words, a culture of non-violence spells a brighter future. Hosam sees non-violent resistance growing, highlighting the active creativity of towns like Bil’in and Budros. “Our work now is to connect the dots. We are one to two years away from a serious national non-violent movement.” HLT seems to be picking up the mantle from an earlier generation of leaders like Zoughbi Zoughbi. Now a member of the Bethlehem city council, Zoughbi has been a long-time advocate for non-violence. He speaks to us from the office of the Wi’am Palestinian Conflict Resolution Center, the rest of the building bustling with young people role-playing and debriefing simulated conflicts. “We don’t want to bring Israel to her knees. We want to bring Israel to her senses.” Seeing the Wall around Bethlehem now complete, he certainly seems more optimistic than the situation warrants. But his energy and that of HLT leave me more hopeful than ever.

HLT seems to be picking up the mantle from an earlier generation of leaders like Zoughbi Zoughbi. Now a member of the Bethlehem city council, Zoughbi has been a long-time advocate for non-violence. He speaks to us from the office of the Wi’am Palestinian Conflict Resolution Center, the rest of the building bustling with young people role-playing and debriefing simulated conflicts. “We don’t want to bring Israel to her knees. We want to bring Israel to her senses.” Seeing the Wall around Bethlehem now complete, he certainly seems more optimistic than the situation warrants. But his energy and that of HLT leave me more hopeful than ever.Wednesday, November 02, 2005

Three Acts

Act I: Lectures. Jeff Halper, Coordinator of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions, and Jessica Montel, Executive Director of B’Tselem, the Israeli human rights organization, both met with us today. Each has keen analysis of the situation. I have often looked to B’Tselem’s thorough reports on the situation of human rights abuses by Israelis and Palestinians as a reliable, fair source of information. Jeff’s work moves far from simply talking about house demolitions to overall analysis of the Occupation. The bottom line for him is that any final peace deal should take into account CVS: Control, Viability, and Sovereignty. If these three conditions aren’t met, then it’s not a legitimate peace. Jeff is also convinced that Ariel Sharon is preparing to make a unilateral move on the West Bank, establishing “Palestine” in the area confined by the Barrier and keeping the large settlement blocs. He predicts that this will happen in the next six months. We shall see how accurate his prophecy is.

Act I: Lectures. Jeff Halper, Coordinator of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions, and Jessica Montel, Executive Director of B’Tselem, the Israeli human rights organization, both met with us today. Each has keen analysis of the situation. I have often looked to B’Tselem’s thorough reports on the situation of human rights abuses by Israelis and Palestinians as a reliable, fair source of information. Jeff’s work moves far from simply talking about house demolitions to overall analysis of the Occupation. The bottom line for him is that any final peace deal should take into account CVS: Control, Viability, and Sovereignty. If these three conditions aren’t met, then it’s not a legitimate peace. Jeff is also convinced that Ariel Sharon is preparing to make a unilateral move on the West Bank, establishing “Palestine” in the area confined by the Barrier and keeping the large settlement blocs. He predicts that this will happen in the next six months. We shall see how accurate his prophecy is. Act II: Settlements. The deep disappointment of the tour thus far is that we were supposed to meet with the Vice-Mayor of Ma’ale Adumim, one of the largest settlements in the West Bank. He called to cancel. Our schedule is so tight that we’re unlikely to be able to meet with him another time, but our tour leaders are trying to rearrange things so that we can. Many of us on the delegation are hoping that we will be able to reschedule. In place of this meeting, several Jewish Israelis took us on a tour of several settlements. One of them was Ma’ale Adumim, a driving tour. It is larger in area than Tel Aviv, though its population is much smaller. Its lush, green lawns are a stark contrast to the arid lands that surround it – Israeli control of water is a major issue. Many analysts, including our guides, say that any final peace deal would likely see Ma’ale Adumim annexed to Israel. Driving around the vast complex and infrastructure, it is difficult to see how it could be otherwise – the mere idea of uprooting this place boggles the mind.

Act II: Settlements. The deep disappointment of the tour thus far is that we were supposed to meet with the Vice-Mayor of Ma’ale Adumim, one of the largest settlements in the West Bank. He called to cancel. Our schedule is so tight that we’re unlikely to be able to meet with him another time, but our tour leaders are trying to rearrange things so that we can. Many of us on the delegation are hoping that we will be able to reschedule. In place of this meeting, several Jewish Israelis took us on a tour of several settlements. One of them was Ma’ale Adumim, a driving tour. It is larger in area than Tel Aviv, though its population is much smaller. Its lush, green lawns are a stark contrast to the arid lands that surround it – Israeli control of water is a major issue. Many analysts, including our guides, say that any final peace deal would likely see Ma’ale Adumim annexed to Israel. Driving around the vast complex and infrastructure, it is difficult to see how it could be otherwise – the mere idea of uprooting this place boggles the mind. Act III: The Adjective Noun. What should we call it? The Security Fence? The Separation Barrier? The Apartheid Wall? If it is a wall, why is it fence in more places than wall? If it is a fence, then why have places that were once fence become wall? If it is for security alone, why is it not built on the highest ground along the most direct route? Why does it snake back and forth, being sure to include settlement blocs and outposts on the Israeli side, as well as Palestinian agricultural land and, therefore, sacrifice security? If it is separation or apartheid, why does it, in places like Abu Dis, run through the middle of town, cutting off Palestinians from Palestinians? We walked along a stretch for several miles where twenty-five feet of concrete loomed overhead and extended far into the horizon. It is a barrier, that much is certain: a barrier to peace, to dignity, to reason.

Act III: The Adjective Noun. What should we call it? The Security Fence? The Separation Barrier? The Apartheid Wall? If it is a wall, why is it fence in more places than wall? If it is a fence, then why have places that were once fence become wall? If it is for security alone, why is it not built on the highest ground along the most direct route? Why does it snake back and forth, being sure to include settlement blocs and outposts on the Israeli side, as well as Palestinian agricultural land and, therefore, sacrifice security? If it is separation or apartheid, why does it, in places like Abu Dis, run through the middle of town, cutting off Palestinians from Palestinians? We walked along a stretch for several miles where twenty-five feet of concrete loomed overhead and extended far into the horizon. It is a barrier, that much is certain: a barrier to peace, to dignity, to reason.Tuesday, November 01, 2005

Hope

Our first stop was in Jericho. The governor, Sami Musallem, is originally from Zababdeh. He has been part of the Palestinian national struggle for a long time, a man with a sharp mind and frank speech. He spared no criticism for anyone, including his own government, whom he said should have done more to reign in extremist elements. But it is clear that the larger obstacle he and all Palestinians face is the Israeli Occupation. While the town of Jericho is subject to the Palestinian Authority, 95% of the region Dr. Musallem governs is under total Israeli control. The area under Palestinian control is just the population area - not the agricultural or industrial lands which that population owns. What struck me most about this man was what he and others represent for the Palestinian leadership as a whole. Despite the corruption and cronyism, the Palestian Authority is peopled with academics, men and women with PhDs from abroad (Arafat, ever the revolutionary and symbol of Palestinian national aspirations, was the exception to this intelligensia). Meetings with sharp minds like Sami Musallem give me hope, despite the desperate situation they face and share. The question for me is whether the Israeli leadership will take advantage of this opportunity to work with those who could lead Palestine into a viable, hopeful, humane, thoughtful future - and, as a result, Israel as well - or whether they will continue to act unilaterally and thus give strength to Palestinian extremism?

Our first stop was in Jericho. The governor, Sami Musallem, is originally from Zababdeh. He has been part of the Palestinian national struggle for a long time, a man with a sharp mind and frank speech. He spared no criticism for anyone, including his own government, whom he said should have done more to reign in extremist elements. But it is clear that the larger obstacle he and all Palestinians face is the Israeli Occupation. While the town of Jericho is subject to the Palestinian Authority, 95% of the region Dr. Musallem governs is under total Israeli control. The area under Palestinian control is just the population area - not the agricultural or industrial lands which that population owns. What struck me most about this man was what he and others represent for the Palestinian leadership as a whole. Despite the corruption and cronyism, the Palestian Authority is peopled with academics, men and women with PhDs from abroad (Arafat, ever the revolutionary and symbol of Palestinian national aspirations, was the exception to this intelligensia). Meetings with sharp minds like Sami Musallem give me hope, despite the desperate situation they face and share. The question for me is whether the Israeli leadership will take advantage of this opportunity to work with those who could lead Palestine into a viable, hopeful, humane, thoughtful future - and, as a result, Israel as well - or whether they will continue to act unilaterally and thus give strength to Palestinian extremism?We arrived in Jerusalem with time to rest and wander the Old City. I arrived at Damascus Gate as people hurried home for the end of today's Ramadan fast. The streets were soon empty. My "muscle memory" helped me navigate the back ways and shortcuts - I was surprised how much I (or rather, my legs) remembered. None of the folks I stopped by to visit were around, which gave me time to visit the Holy Sepulchre. The lines going into the tomb were long - longer than I had seen them in some time. The tourist trade has clearly picked up again. By the time I headed back to the hotel, the streets were vacant. Some merchants stood in their doorways munching on sandwiches or plates of traditional msakhan.

Our final event of an already full day was a visit from Rami Alhanan, an Israeli who volunteers with Israeli Palestinian Families for Peace. The organization is for those who have lost children in the conflict, but use that pain as a moment of transformation. "I am angry. I am still angry," he shared with us. "But when speak with a class full of children and see one child nodding his head, I know that at least one drop of blood will be spared." Rami's story of losing his daughter to a suicide bomber is extremely powerful and moving - but his words are more eloquent than mine (follow the link to a World Vision interview with Rami). His closing words rang in our ears:

Our final event of an already full day was a visit from Rami Alhanan, an Israeli who volunteers with Israeli Palestinian Families for Peace. The organization is for those who have lost children in the conflict, but use that pain as a moment of transformation. "I am angry. I am still angry," he shared with us. "But when speak with a class full of children and see one child nodding his head, I know that at least one drop of blood will be spared." Rami's story of losing his daughter to a suicide bomber is extremely powerful and moving - but his words are more eloquent than mine (follow the link to a World Vision interview with Rami). His closing words rang in our ears:I am the son of a Holocaust survivor. The world stood by and watched. Now, in this place, two people are killing each other. The world is standing by again, and even giving support to one side. But you, your presence, give us hope.

Marthame Sanders lived in the Palestinian Christian village of Zababdeh with his wife Elizabeth from 2000 to 2003.

He is a Presbyterian minister and president of Salt Films.

Marthame Sanders lived in the Palestinian Christian village of Zababdeh with his wife Elizabeth from 2000 to 2003.

He is a Presbyterian minister and president of Salt Films.